The Year of the Brush

Politics aside, I tend to think Bono was right, “Nothing changes on New Year’s Day”. I mean, can salt be made salty again? Can an old dog learn new tricks? But on December 31st, 2016 I declared the next sunrise would inaugurate “The year of the sketchbook”. A year later I tallied 248 sketchbook pages I had filled in the ensuing span. More disciplined artists might shake their heads at such a paltry count, but that number still makes me do a double-take. The trend dropped off in 2018 which was slammed with work, but the occupational benefits of such uncharacteristic mobilization of the will were quite noticeable. Keeping a sketchbook especially when assignments are scarce is like keeping the stream flowing, not letting it become stagnant. I call it “recreational discipline” but if it can be elevated to habit, so much the better. (The next level up is Zen but by then you’re already getting mail from collection agencies).

If nothing changes on New Year’s Day, at least all is quiet. As sacred as Christmas is, once the festive clamor of the holidays settles down and you can actually hear yourself think, something else preternatural about the season often stirs the creative pot, gets the muses whispering. To quote another favorite (from an earlier era), “Later on we’ll conspire as we dream by the fire”. This January 1st, 2019 another resolution moniker dropped into my coffee, “The year of the brush”. It was time to leave the (nerd alert) safe, predictable Shire of graphite and paper for the more perilous Middle Earth of oil and canvas.

Don’t get me wrong— I’m no stranger to the easel, where I’ve dispatched my share of assignments. But in the digital age it’s easy to go weeks or even months without setting foot in the old school. The last few years I’ve cranked out about as many traditional paintings as your average forensic accountant. But somewhere in the January quiet, I could hear my muse nudging me to confront my old nemesis, color, the old fashioned way. I often feel I have about the same color intuitions as my cat Ginger (photoreceptive cones notwithstanding). I know this isn’t true, but because of the complexity and nuance of color, my experience of painting is often like what Stephen Covey says about air travel: “the plane leaves and arrives on schedule but due to weather conditions and other factors is off course 90% of the time”. Getting the darks/values going is simple enough and the finishing touches almost offer themselves to you. But everything in between belongs to turbulence, technical malfunctions, crying babies, and the occasional hijacker. For an illustrator working on a deadline, this is about as welcome as having to sanitize the entire lavatory just so you can relieve yourself at 30,000 feet without contracting septicemic plague. But while I default to the comfort of a 4B woodless pencil (or the safety of Photoshop layers) it’s color that really captivates me. The combinatorial possibilities are endless, and endlessly delightful.

So before they could even hoist the ball back up to it’s perch in Times Square, I was already achieving mud on the palette. Trying to remind myself about graying with complimentaries, the dynamics of warm and cool, where those damn pliers are so I can get these ancient paint tubes open.. But something was beginning to happen. My steadfast mentors, Trial and Error, were reaching over my shoulder, guiding my hand, quoting Yoda, “you must unlearn”. See, I gravitate to oil not only because of its buttery, transcendent properties and the centuries of high cultural tradition but because it doesn’t punish with finality like watercolor or acrylic. One doesn’t hear the sound of “bolting and double-bolting” after each stroke. There’s no “command-Z” but it is relatively user-friendly, a quality this artist appreciates— not simply with the goal of avoiding failure, but precisely to welcome and learn from it. As Andrew Wyeth said, “Creativity is allowing yourself to make mistakes. Art is knowing which ones to keep.” With persistence those “mistakes” become tools in your toolbox. You keep them, not only on the canvas but in your repository of ideas. They are grafted into your process and, if I may add one more metaphor, eventually become part of your “voice”.

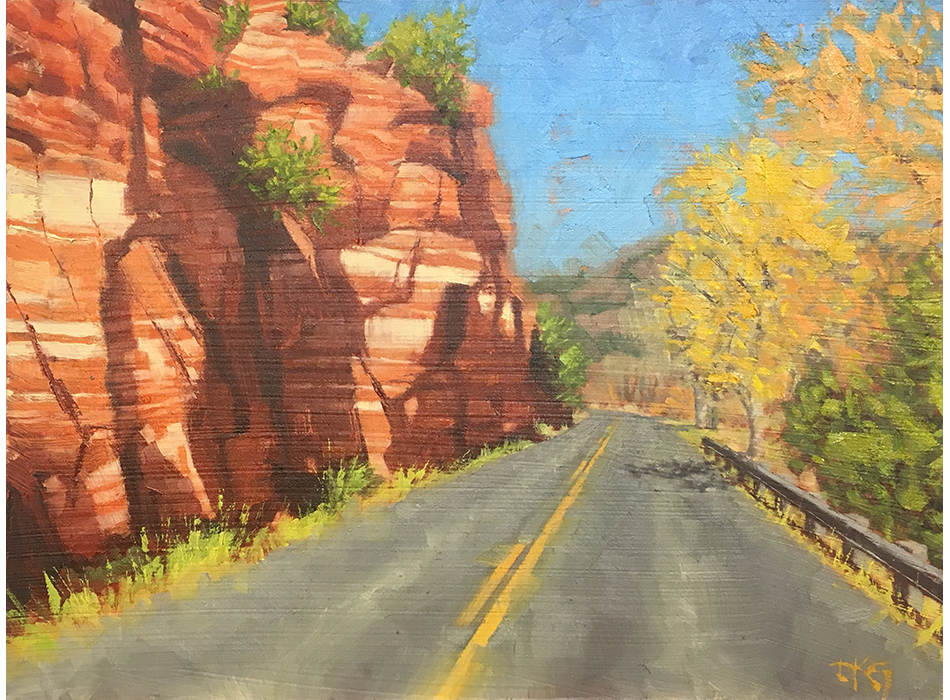

Conduits of Beauty

I had set the highly achievable goal of one painting a month, though I knew this would be far from effectual (unless we’re talking large murals, and we’re not). The studio started smelling of old school creativity and I churned out a handful of small landscapes, mostly from photos I had taken on family trips. But I also began to get a hankering to take the operation outside. See if you can relate to this— you’re looking at a 4x7 of the Grand Canyon. You’re painting an 8x10 of the Grand Canyon. You’re standing on a tile floor in the the air conditioning of your 12x14 studio and you’re cranking up the podcast to drown out the incessant buzz of your neighbor’s weed-eater outside your window. You keep getting texts every few minutes, the kids just clamored in from school, and the cat is howling to go back out. Is something missing here? Something, perhaps.. Grand? I remember a Ballard Street cartoon captioned, “Sometimes life is like looking at a blazing sunset through a bug-splattered windshield.”

Speaking of the Grand Canyon, a few years ago we backpacked down to Phantom Ranch, spending three days and two nights below the rim. I had longed to make that trek for years, knowing that the full plunge would be orders of magnitude greater than snapping photos at the guardrail. And I was right. In the annals of family vacations, even for my kids this trip remains the favorite— even over Disney World! In The Weight of Glory C.S. Lewis said, “We do not want merely to see beauty, though, God knows, even that is bounty enough. We want something else which can hardly be put into words — to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.” This is a human trait, not merely an artistic one. Yet there is something pure and primal about plein air painting (alliteration aside) that nourishes the artistic soul in a way painting from a photograph in the climate-controlled confines of the studio never can. This is also true with life drawing, not to mention photography itself: We encounter beauty—feel it—“pass into it” and we want to tell the story, but through our own lens—in our own voice. We become conduits of beauty, making it accessible to others. Perhaps the age-old impulse to make two-dimensional images stems at least in part from the very fact of our three-dimensional existence. If I may wax theological for a moment we, being image-bearers of God, by our very ontology (ie. by our human being) are transcribing the Higher to the Lower. It’s vertical. To be clear, I make no qualitative implications here—I work from photographs all the time. It is perfectly legitimate. But with a photo as our starting point we can sense that something very elemental has already been done for us. In general, drawing or painting from photographs is academic. Drawing or painting from life is existential.

The Plein Air

In my giddy new obsession I annexed a lightly used french easel and for it’s christening I found a secluded spot on the charming Piedmont trail north of town. Since I find the idea of painting in front of an audience about as inviting as a colon irrigation, the relative solitude of Piedmont was ideal. And the entire thing is in the shade, thereby not aggravating my twenty year demons of heat exhaustion. My expedition lasted about two and a half hours, until it was dark enough to start calling it a blind contour. And after tinkering about another hour in the studio I was reasonably pleased with the results. The whole experience was rather delightful with the exception of the easel’s thin nylon shoulder strap all but dissecting my trapezius muscles. The French easel is a wonderful invention, but it’s far from ultralight. Taking one of these on the trail is a bit like running a Suburban through the slalom course. (The next level up will be the tripod and small paintbox combo.) But I dug out my dad’s old Camp Trails external frame pack (circa 1973) and “repurposed” it’s shoulder and waist straps which anchored quite nicely to the french, making it much more ergonomic. I could now arrive at my painting spot and actually feel my hands.

A few weeks later my eleven-year-old, Singer-London and I set out for a camping trip (her idea, honest!) to Hagan Stone, our old family haunt, and we were both looking forward to a little plein air action. (Plein air is a French term that simply means “in the open air”— painting outdoors.) We had a grand time.. we biked, we hiked, we threw frisbee, played at the playground, cooked hotdogs over the campfire, contemplated the meaning of life.. and, being my sketch-pixie-nerd, she was as excited as I was to get out there and paint. Now as you might expect there is, ahem, some preparation to such a venture. But I mean, how hard can it be? ..A tent, a couple of sleeping bags, some hot dogs, water, bikes, matches.. the french easel and brushes.. Am I missing anything? So imagine driving, camping, then hiking to your plein air spot only to realize you had forgotten all your paints. What the— Yep. Cut to a still shot back in the studio of a pile of paint tubes sitting obediently where I had left them by my drawing table. Then back to me, glancing helplessly at my daughter, who is looking back at me with no surprise whatsoever. There's a little jingle in my house (to the tune of Billy Goats Gruff) that goes, “Wouldn’t be Daddy if he didn’t come back”. Whenever I leave the house, the kids practically count the seconds until the door flies open and I swoop in to grab whatever I forgot this time. Now sometimes the lesser of two evils is to just play the hand you’re dealt. Thankfully, we had made a pit stop on the way out of town where I picked up three new tubes: burnt sienna, sap green, and cadmium yellow light (otherwise I would've been painting with coffee, sunscreen, and creek water). And thanks to the presence of white in the cad yellow, I had one relatively opaque color in the trio, meaning it wouldn’t simply be a sketch. In the end it was a “happy accident” (because what would an art blog be without a Bob Ross quote?) as it forced me to entertain a limited palette—my Achilles heel, and I honestly wasn’t disappointed in the outcome. To return to the airplane analogy, I would rule this one a crash landing, but a landing, no less.

Sing and I had a fabulous time plein airing (check out her amazing watercolor). We traded the predictability of the studio, the air conditioning, the weed-eater, the restless cat syndrome— for fresh air, the smell of campfire smoke, the er, uh humidity, the sunburn, the mosquitos, the tics (two), my old Audi’s electrical gremlins (the alarm goes off whenever it damn well pleases—whether or not it’s locked), and gloriously— the hand we were dealt. It’s well worth the sacrifice, the discomfort to take your vocation out the door, whether it’s sketching at a coffee shop, painting in a hay field, or embedding with an Air Force unit in Afghanistan (due to deadlines and bad timing I regretfully passed on just such an opportunity years ago). Like me, you probably have mouths to feed, a spouse to appease, and the gods of middle age entropy not to provoke.. But get outside, challenge the elements, challenge yourself. You’ll be the better for it. Do it with one of your most favorite people in the world and you’ll have an experience that’s far greater than the sum of its parts.

Breaking Through

As of this spring David Stanley Illustration has been in business for 25 years and what a wild ride it’s been. I’ve been on assignments all over the U.S. and five other countries in three different hemispheres. I’ve had the privilege of working for a slew of amazing companies and collaborated with countless brilliant people. I’ve experienced the peaks and troughs of operating a business for a quarter century and produced more art than my house (and hard drive) can hold. But self-employment is a bit like the Flintstone’s car— a perpetual motion machine it ain’t— so keep your feet moving! And being an artist means constantly reaching deep to make something new, something compelling, regardless of one’s past accomplishments.

It also means occasionally forsaking the comfort zone, exploring unfamiliar territory. I don’t know if old school painting is my destination for the foreseeable future but it has sure been invigorating thus far. By the end of May I tallied twelve paintings, more than twice my goal and enough to say I’ve kept my New Year’s resolution to date. But it’s not enough. It’s never enough because the past hardens behind you like quick drying cement and if you don’t stay a step ahead, you get stuck in it. I realize I’m still just scratching the surface. Just scraping the palette. And speaking of which, there’s one right here that needs scraping and cleaning. The year of the brush is really more like The year of cleaning a fist-full of brushes several times a week. But that’s a small price to pay for the privilege of getting to draw and paint as a vocation.. for the honor of telling the story of God’s beauty in creation through the endless mystery of color.

“Say it’s true, it’s true. And we can break through. I, I will begin again.”